"Farol"

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX- Milongueros Ernesto Delgado and Miguel Balbi

Well, this is it. We have arrived at the summit. I may have been a little hard on Troilo and Fiorentino on the last page... after all, who am I to find their version of Encopao lacking? Almost every great milonguero would put Troilo at the top of the list. The maestro of maestros. It took me awhile to figure out why… but the answer is right here! This is the tango they were dreaming about in Emoción:

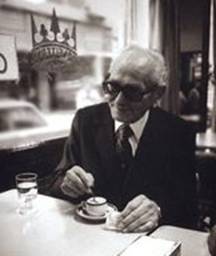

Anibal Troilo

Where do we start? The words are almost achingly beautiful. Simple… but also complex. (Yeah, right… but that’s how I feel it.) They paint a picture of the poor neighborhoods that surround the city (in this case, probably Boca or Barracas), and of the souls of the people that live in them. This tango is performed with so much technical skill that it becomes almost the perfect “union of notes and words” that is eulogized in Emoción. I’m no musician (far from it), but my untrained ear hears Troilo and Fiorentino using almost every tool they have. They vary the tempo, the volume, and the tone in a way that creates something so powerful and moving that you can dance to it for years, and still find something new. The best dancers all seek that indescribable thing that tango has. The milongueros call it “entrega”... and if you can’t find it here... you won’t.

What do the lyrics mean in English? The actual words aren’t that difficult to translate, but Homero Expósito’s message takes a little thought. Let’s look at the first couple of verses (Note: a “farol” is an old fashioned type of street lamp that hangs from buildings and is mounted on lampposts in Buenos Aires):

A neighborhood of poor houses

reflecting the colors of their tin walls…

a human neighborhood,

with its stories sung in tangos.

And in the distance,

a clock strikes two in the morning.

A working neighborhood...

a street corner of memories

...and a farol.

Un arrabal con casas

que reflejan su color de lata...

un arrabal humano,

con leyendas que se cantan como tangos.

Y allá un reloj que lejos da,

las dos de las mañana.

Un arrabal obrero...

una esquina de recuerdos

...y un farol.

This is poetry. In Farol, Expósito paints a picture of the birth of tango: Of poor immigrants, hard work, beauty... and of things that will never return. There are night shadows under a street lamp, and shadows in the alleys at 2am. A sleeping neighborhood with the “dreams of a million working people” floating up into the night sky. Dreams are “murmuring on the night wind”—while tango lurks in the shadows.

“Vengan a ver que triago yo…” says Campos. “Come and see what I bring with this union of notes and words.” Sorry, I have to say it again: This is simple, but it’s also complex. Just as Campos tells us in Emoción, a tango is the sum of several parts. A guy sits in a café at night and dreams some words. Maybe he reworks them and polishes them up a bit. Then someone else reads them, gets inspired, and writes some music—a tune with cadences. Different people play it, rearrange it, sing it, and dance to it—each time in a little different way. And finally, we arrive here.

Let’s listen closely to where Troilo takes us before the singing starts. The opening is a little nervous—a crowded neighborhood going about its business. Then he quiets the orchestra as the sun sets, and the shadows come out (at 00:33). We wander the neighborhood… and then there is a rush of emotion: “La sombra!” (“The shadows!”)—at 00:45. (This is before the words begin, but we know “the shadows” belongs here, because it’s sung to the same music later, at 1:50.) When Fiorentino does begin to sing, Troilo quiets the orchestra again… but it’s still there. CHUNK-chunk-CHUNK-chunk. Piano-bandoneon, piano-bandoneon. Dos por cuatro. Nothing more. Finally, the complex mix of singer, orchestra, and poetry begins in earnest. Let’s look at the second half:

Farol...

the things that can now be seen.

Farol...

not the same as yesterday.

The shadows…

today they escape your gaze,

and leave me more sad,

in the middle of my short street.

Your light, with the tango in its pocket,

was losing its brilliance…

and is a cross.

Farol...

las cosas que ahora se ven.

Farol...

ya no es lo mismo que ayer.

La sombra…

hoy se escapa a tu mirada

y me deja más tristona

la mitad de mi cortada…

tu luz, con el tango en el bolsillo

fue perdiendo luz y brillo…

y es una cruz.

[These last two verses of the poem aren’t included in Troilo’s version]

The sky speaks

with the dreams of a million workers…

and the wind murmurs

with the poetry of Carriego.

And in the distance,

when the clock strikes two in the morning,

the sleeping arrabal seems to repeat,

“Farol…”

Allí conversa el cielo

con los sueños de un millón de obreros...

allí murmura el viento

los poemas populares de Carriego.

Y cuando allá a lo lejos dan

las dos de la mañana

el arrabal parece que se duerme repitiéndole

al “Farol… “

This tango is heavy on symbolism—beginning with the farol, which is one of the most famous icons of tango. It also has the arrabal, tin houses, poor people, the street, and even a cross. I suppose a work of art can mean different things to different people. For me, “Farol” is like a great painting—you don’t have to look closely at every brush stroke to appreciate it. But I’ve been thinking about the words for awhile, and I’d like to talk about what I think they mean, because Expósito’s poem is addressing the greatest theme in all of tango: nostalgia.

Nostalgia is made up of both wisdom and delusion. Sometimes things in the dim past actually were better… and sometimes they weren’t. Of course, it’s usually difficult to really know either way. Homero Expósito understood this very well, and it seems to me that his subject in “Farol” is the meaning of nostalgia itself. Expósito’s streetlight represents nostalgia—it's the warm light of memory that we use to look into the dark past. It illuminates some things, but it also distorts, and it leaves some things hidden in shadow. It bathes the rough edges of the past in a warm glow that may or may not be “real”. Either way, we certainly have a different perspective than the people who were actually living in this old neighborhood, because not only are we gazing back through the years, but we are also taking our tour through the streets at the tranquil hour of 2am, when everyone is asleep and dreaming.

Expósito is saying that the warmth and tranquility of our viewpoint is, at least in part, an illusion. He knows that life in the old arrabal was (in the words of Thomas Hobbes) “nasty, brutish, and short”. People were packed together in conventillos, they were working themselves to exhaustion, and for most of them, dreams were the only things that they actually owned. But he also recognizes that through the light of memory, we can now see things that they could not. There actually was humanity and grace... and there was also glory. Because we now know that it was the desperation of the arrabal that made Argentina. Not only did the people of the arrabal literally build Buenos Aires out of bricks and mortar, but through their struggles, they also gave birth to that unique union of music and words that captured the imagination of the rest of the world. Of course, at the time, none of them could know it.

There are some very nice images here… light reflecting off of the houses, clocks striking in the distance, and dreams and poetry floating on the night wind. But what about the “cross” mentioned at the end of “Farol”? Well, that part drives me crazy. It could have religious implications, and you could even use it to draw some connection between religion and tango… but I don’t think so. Religion has never been part of tango, and I don’t think Argentina is an especially religious country. Argentina is Catholic, but I don’t get the feeling that religion permeates things here in BsAs—at least in the way it does in other parts of Latin America . The Mexicans who live around us in the U.S. seem to live in an almost surrealistic world in which a mixture of the old tribal religions and Catholicism affects almost everything they do—but I think porteños are more interested in psychoanalysis and real estate development than they are in lighting candles to the different saints. (We live in a part of town people call Villa Freud. The name is a tongue in cheek reference to the many Freudian psychoanalysts who live and practice here—but then one of the oldest and most beautiful Catholic churches in the city sits right in the middle of our neighborhood as well.)

Here’s my favorite guess: Maybe the cross in “Farol” represents fate, rather than faith. In Argentina, instead of calling the two sides of a coin “heads” or “tails”, they use “cara” or “cruz” (“face” or “cross”). So maybe the “cruz” in the pocket represents a coin, and the cruz represents one side of it. The toss of a coin. Luck. Because people in old-time BsAs were living on the edge. The Yellow Fever in 1870 almost wiped everyone out, and there was certainly no way for the poor people to know what the future held. It’s nice to look back through the warm light of the farol and see something glorious being born, but at that time, survival was far from certain. A few small things happen in a different way, and the coin comes down on the other side…“cara” instead of “cruz”…and they could have all just faded away.

Okay, that’s a stretch. Maybe the most obvious explanation is the best, and Expósito is simply saying that the fading of our memories is a “cross”, a “burden” that we have to live with, as the inspiration for the birth of tango fades into the past. Anyway, I like the coin toss idea.

****

The truth is there was a time when I didn’t like Farol all that much. Here is another version of it by the other great maestro of tango:

Osvaldo Pugliese

Draw your own conclusions. Pugliese’s version is probably the better known outside of the milongas, and it’s very nice—but I heard it for years without ever wanting to dance to it. To me it seems more suited for Teatro Colon. I think Troilo’s version has a little harder edge, and Chanel’s voice is no match for Fiorentino’s. It was only after DJs in BsAs like Natu and Dany exposed me to Troilo’s Farol that the tango really seemed to come alive for dancing.