Making Tango Work

The more I dance and learn, the closer I move toward one very simple idea: In the end, tango is nothing more than friends gathering together to share the music. It all begins, and ends with that. Tango is loving the music, and caring about each other. That may sound a little “new age”, but it’s true. Another way to put it is that the continued existence of tango requires a respect for the music, and a respect for each other. If you have an environment where those two things exist, then you can celebrate tango. If you don’t, then you can’t. If you have instructors who, both by example and word, are committed to teaching students how to navigate and dance in a way that doesn’t bother other dancers, then you can have milongas. If you don't, you can still have classes and practicas where people work on steps and figures—but that's all you'll have.

Let’s continue with our discussion of navigation. We'll look at some things we see people doing all the time that don't work in crowded conditions. I think most of these dancers are trying hard to fit in—but even when they're not bothering anyone else, they often look frustrated. They look like they're not really having much fun. The first kind of tango that doesn't work well in a crowded milonga is...

Square Corners

This kind of dancing is built around the "8-count basic" step pattern. We sometimes see it today in older couples. They're often very polite on the floor, but their dancing has too many sharp edges. I say older couples, because this is probably the first type of tango taught in classes, and because many young people prefer a newer version of figure based tango. This tango is from the 1990s. It think the Dinzels popularized it, and it's surprising how many big names in tango today began with them. The Dinzels came to tango from Argentine folklore, and their approach was to identify as many elements as they could, give them names, and then link them together with rectangular step patterns. This kind of early academic tango looks somewhat out of date today, but there are still lots of instructors teaching it. I'm familiar with it, because it's the way I began learning tango:

The Dinzels and Osvaldo Zotto demonstrating tango based on step patterns.

This step-pattern tango provides a kind of order and security that's perfect for classes. There are routes to follow, and small figures with different names—and places to pause and perform them. The patterns look almost like circuit diagrams. This is what they might look like on a crowded floor:

Obviously this kind of dancing is a disaster in a milonga. You sometimes see couples that have learned this tango standing in one spot, waiting for enough space to complete their pattern.

Separate Barrios

This is the classic tango of performers. I've used the words "park and perform" or "pause and pose tango" to describe it. I also like the term "everybody's a star" tango—but then, I'm a smart-ass. It's tango that focuses on elaborate, stationary choreography:

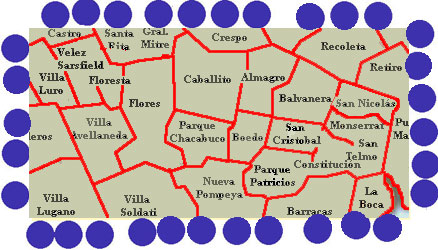

This tango not only requires rehearsal by both partners, but it also uses large amounts of space for extended periods of time. The problem is that if everyone begins to use more than their normal share of personal space (see page 36) for more than a few beats of the compás, everything will grind to a stop and the floor will begin to look like it's been divided up into a map of the BsAs barrios:

The pattern on this map is fine for practicas, where people are expected to stake out their own areas to work on things. For a while in the U.S., there seemed to be the belief that it was okay to take space in the middle of a milonga to do stationary figures. But we're talking about crowded milongas, and in a crowded milonga, the center of the floor needs to circulate just like the rondas that surround it. (I remember walking into a large milonga in the U.S. once where people were circulating more of less normally—but a well-known ballroom couple was doing exaggerated poses in the middle of the floor. The woman would raise her leg way up high and hold it. Or they would embrace, sink down to the floor together, and then slowly come back up. The effect was creepy. It looked like a queen bee surrounded by drones, slowly circling her as she postured and performed. Or like some ancient Aztec ritual.)

Steppin' Large

There's a young guy who has been showing up at one of the milongas we go to. He's a good dancer, and he's respectful of everyone. But he has the academic dancer's habit of taking the same big, dramatic step all the time, and it causes lots of problems for him. He's like a guy who spent a lot of money on a big, fast car with high gears, but has to spend most of his time on winding roads. Or stuck in traffic. Small taxis and motorbikes whiz by, and he can barely get out of first gear between the traffic lights.

The solution for him would be to realize that big steps are very nice—but so are little tiny steps. In fact without little steps, big steps don't mean much. Even changes of weight from one foot to the other that don't go anywhere can be very expressive. The art is in varying the mix. And the highest art is to use these variations to creatively express the music, and skillfully navigate the floor at the same time. The challenge of sharing tango close to other couples that understand this is one of the great pleasures of tango. It's the opposite of bothering other dancers, because it actually adds to everyone's enjoyment. I won't include a video example of large-step tango, because it's fairly self-explanatory. But I do have a vision in my mind of what tango should look like. We'll stick with our BsAs theme, and represent it this way. This my mental picture of the kind of movement Alej and I create when we dance—of the path we might follow:

I think of the path we follow on the floor of a milonga

as looking something like these traditional BsAs firuletes.

Firuletes

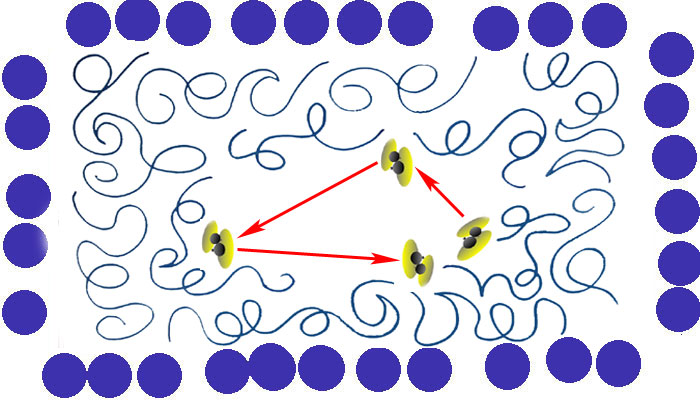

Finally, here's how our milonga might look when people use the compás to curve the paths of their dancing. It's a mix of different step sizes, occasional pauses, and curving runs that fuse into giros. For me it's the perfect way to express the hard-soft of tango. I think if you look at the video of most of the great dancers we've put on the site, you'll see floor movement that looks something like the blue lines here—something like the traditional firulete art that decorated Manoblanca's cart:

The yellow couple is stopping to perform figures,

and taking big steps. The blue lines

represent the paths of couples that are dancing curved corriditas, or "curved-runs".

Obviously the yellow couple is having a tough time. They represent the young guy who tries to dance by stopping to perform figures, and then using large steps to move to a new place on the floor. You might look at this pattern for a minute, and think about which paths come closest to representing a physical expression of the music.