Form Follows Function

“The fundamental failure of most design is its insistence on serving

the God of Looking-Good rather than the God of Being-Good”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx-R. S. Wurman

What makes tango different? As we studied the dancers of Buenos Aires, it became more and more clear that the tango we see today did not come from people practicing in studios. Tango didn’t come from people inventing steps in dance classes, nor did it come from choreographers designing performances for stage entertainment. Argentine tango, both its origin and its creative core, begins and ends in the clubs and the streets of Buenos Aires. Tango (both tango dancing and tango music) is the direct result of the special conditions that exist in Buenos Aires . It was born there, it grew there, and, the dancing continues to evolve there today.

For this reason, any attempt to understand the nature of the music and the physical movement of tango must begin there. So in this section, I would like to present a few examples to support the argument that the form in which tango is danced today is a practical and efficient design that has evolved for more than 100 years in the unique and splendid isolation of Buenos Aires . Almost like a discreet ecosystem on a remote island, tango is the happy result of trial and error. A natural system in which bad designs die out and new and efficient ones prosper.

Crowds & Bandoneons

Masters of navigation: 28 milongueros dancing comfortably in a single car garage.

There are two huge influences on tango dancing—two special conditions isolated in Argentina that have affected everything—the posture, the walk, the embrace, and the cadences, figures and patterns of tango as well. They are: crowding, and the bandoneon. Anyone who’s been to BsAs knows how crowded it is in milongas, and the old picture above shows that the crowds have always around. It’s always a shock to leave tango classes and discover the harsh reality of the milonga. Dreams of dancing like Pablo Veron on that empty floor in the movie are shattered… and many students never recover.

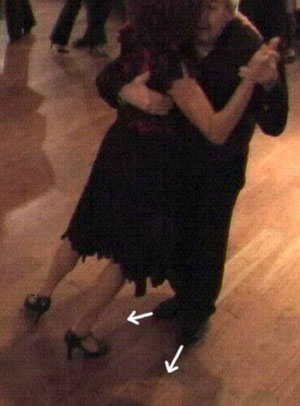

Movement in crowded conditions requires two basic things: the ability to stop, start, and change direction easily (maneuverability), and the ability to remain stable and secure when the inevitable bumping occurs. Look at the way the milongueros in the following pictures are standing:

Five well-known milongueros from all over Buenos Aires are pictured above. Top: Pocho who dances mostly downtown (at Lujos). Bottom row: Osvaldo Buglione (at El Beso), Julio Duplaa (at Sunderland), El Chino (at Sin Rumbo), and Tete (at Banco Provincia). [All dancing with Alej]

One afternoon in Region Leonesa, Pocho came over and told me, “You shouldn’t stand with your feet parallel. It’s better to point your toes out like this: \ / . The diez y diez (ten minutes after ten on a clock face) position is the most stable. No one can knock you down.” Pocho is one of the most respected tango dancers in the world, so of course I paid attention. I began to look around, and I noticed that almost all of the good dancers were standing this way. Because milongueros must sometimes pause to avoid collisions, often in very tight spaces where the risk of bumping is highest, stability is important. So, these dancers, all from different barrios of BsAs, have all evolved into the same stable \ / shaped, toes-out stance to deal with the problem. Even Tete, whose toes naturally point inward, does it. So there is the first evidence that form follows function in tango. The form of the stance is a direct result of the need to maintain balance, remain secure, and protect the woman from the jostling of crowded conditions. As we will see, this is a theme that runs through tango over and over.

“Form follows function” means that when something works well, it begins to look good. (Alej has warned me about using sports analogies—but I can’t resist). Forty years ago, skiers used a very upright, feet together stance, with their arms held casually at their sides. This was considered very elegant—and gliding gracefully down groomed slopes with their skis locked together like Stein Ericson was everyone’s idea of perfection. Today, the best skiers use a more crouching, feet apart, arms out style—a stance that used to be considered the mark of bad skiing. Because of this more efficient, athletic position, skiers today can ski more of the mountain at higher speeds than ever before, and this technique has become the one everyone aspires to. Like the tango of the milongueros, it is a sort of rough art that is beautiful because it works.