The Limits of the Music

Just for fun, let's look at the wave graphs of the three different “styles” of tango we’ve discussed:

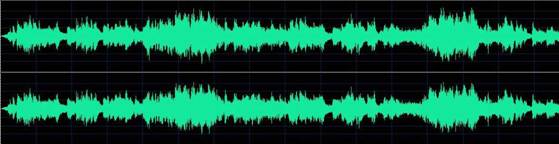

El Cencerro’s wave graph reveals the hypnotic, traditional compás of D’Arienzo.

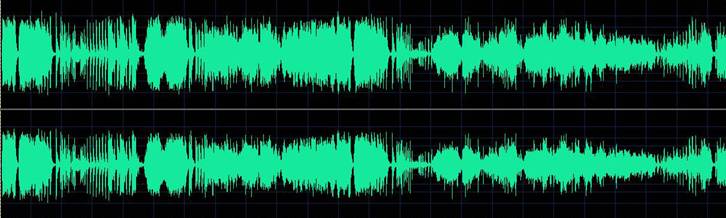

This graph shows the smooth, full sounds of De Caro’s orchestra in Flores Negras.

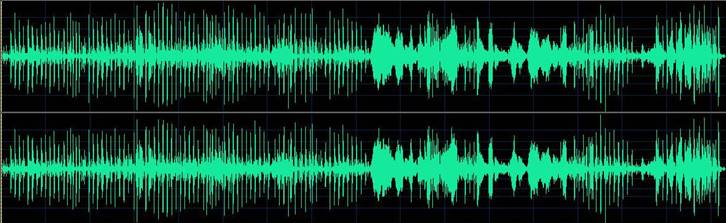

Today in the milongas, some of the most interesting (and also challenging) tangos have a mix of both sounds. Let’s look at a graph of Troilo’s Suerte Loca (“Crazy Luck”):

Troilo uses a brilliant mix of strings, cadence, and voice, in Suerte Loca.

In Suerte Loca you can see how Troilo starts with the full orchestra (on the left half of the graph), then begins to alternate with solo bandoneon cadences (the sharp spiked sections in the middle of the graph), and finally mixes the singer, and the bandoneon together (at the end of graph). (Note: This tango is translated and discussed in detail on page 14)

YES! These guys knew what they were doing! The sharp spikes in the top graph show the sharp “CHUNK–CHUNK” of D’Arienzo’s bandoneons in Cencerro. It’s easy to see how amazingly consistent and symmetrical they are. The second graph shows the “smoother” waves of Flores Negras. The full sound of De Caro’s orchestra fills in all the gaps, leaving a filled in wave pattern, and burying the compás under the melody of the strings and piano. Finally, look at how Troilo first alternates, and then mixes both styles in Suerte Loca. The sound waves on the graph fill in when he uses the full orchestra, and then the sharp dos por cuatro spikes return when he lets the orchestra rest. In the end, he backs up Fiorentino’s voice with only the bandoneons. This last graph shows a very interesting mix that is used in some of the most popular tangos today: full, rich melodies by the entire orchestra, alternating with the primitive driving rhythms of the street. For me, this is a beautiful, classic format that can be very challenging to dance to. It’s not surprising that Troilo’s masterpiece, Quejas de Bandoneon (“Wail of the Bandoneon”) is so often used for concursos (dance contests with small monetary prizes) in the barrio clubs. Its range stretches the abilities of the best milongueros to respond to the music:

Here are the last two graphs (I promise):

The waveforms of Troilo’s Quejas de Bandoneon are almost chaotic…

which shows why it’s so difficult to dance to!

Finally, here is Pugliese’s masterpiece, La Yumba.

The complex challenge of dancing to Troilo’s Quejas is revealed in the top graph, while the bottom graph shows that Pugliese was the maestro of hard-soft. His music contrasts the cadences of traditional tango with the more complex use of strings and piano that was pioneered by De Caro. The graph of La Yumba above illustrates this very clearly: hard bursts of sound on the left, softer sounds on the right, and then some alternating and mixing toward the end. Notice how high Pugliese’s cadences spike on the left half of the graph, which indicates how intensely he marks the compás. D’Arienzo may have achieved the longest consistent run of pure cadence in El Cencerro, but Pugliese probably attained the sharpest, most intense cadences in La Yumba.

The first time I went to Buenos Aires I watched Los Reyes de Tango perform La Yumba in a milonga. I was standing to the side of the orchestra, looking down the front row of five bandoneonistas, and I’ll always remember it. They were bobbing, rocking, jumping, twitching, sweating, and pounding away—putting everything they had into giving Pugliese what he wanted. They were working so hard that they looked more like laborers laying railroad track than musicians.

If you listen to the old guardia vieja tangos, you should find that their cadences were a little slower and softer than the ones used later. Troilo’s bandoneon and Biaggi’s fingers on the piano were noticeably quicker and crisper in the newer tangos—but none of them matched the intensity of La Yumba.

How did Pugliese do it? Well, the answer is in a movie called “Si Sos Brujo” (“If you Were a Wizard”— admittedly, not a good translation). If you’ve made it this far through these pages, then you must see this movie. It’s hard to find, and it’s in castellano… but it’s worth the effort. Si Sos Brujo is about a search for the musical techniques of the old maestros, and the reawakening (almost the rebirth, really) of a very sweet and funny old man—the maestro Emilio Balcarce. And it ends, as all good things should, with a moving rendition of La Cumparsita.