Walking (Part II)

Moving Efficiently

Efficiency is a beautiful thing. In fact, I like it more than beauty created just for the sake of beauty. To me, something that solves an engineering problem, like a fast airplane for example, is often more “beautiful” than many sculptures. That’s probably why I think the efficient tango of the milongas is generally more attractive than stage tango. And it's why I prefer the classic, practical walk of the milongas, rather than more stylized movement designed to attract attention. So let’s talk about efficiency of movement.

In some ways, walking in tango is easier for me than the slouching inefficient way I walk around the street. One reason is that a good tango walk conserves energy. Think about the walk we're discussing. Which muscles do we need to use? If we stay centered and balanced, we're using the minimum number of muscles needed to remain erect. Keeping the arms still eliminates more muscle use and wasted energy. And what about the legs? When I walk in tango, my leg remains straight all the way through the step. This is when it carries all of my weight, so not flexing it saves more energy. And the other leg requires just enough energy for me hold it a few inches off the floor as it swings forward for the new step. Nothing more. Compare it to the amount of movement in the show dancing on page 3. The show dancing displayed there burns so much energy that it probably contributes to global warming. I suppose the choice between the two ways of dancing depends on your priorities. If you want a workout, the tango on page 3 is the way to go. If you want smooth and efficient movement, the walk we're discussing here is better.

Two video captures of Fino dancing in a milonga. They come from

15 seconds of film that is only record that exists of his social dancing.

But of course, there's more to dancing tango than just conserving energy. I mean, if energy conservation were our only goal, we could just sit at the table and tap our fingers to the music. Efficiency means doing something in the easiest way possible, so if we're going to use it to describe tango, we need to know exactly it is we're trying to do. What exactly is the tango problem we're trying to solve? We'll, I think the technical problem we all face as tango dancers how to physically express the soul of the music—and the very core of that physical expression comes from the dos por cuatro of the compás. The 2 x 4 rhythm of tango. Before we can express anything else we may feel in tango, we need to be able to express the dos por cuatro of the music. Let's see how our walk can help.

Physics and Harmony

A large part of tango is hidden from us. If you divide learning tango into three parts using the jazz model (learn the music, learn your instrument, then throw something away and learn to play), two of the parts have spiritual elements that, in the end, are beyond understanding. We can listen to music, and play music, but there is an artistic element that will always defeat rational analysis and understanding. However the third part, learning the mechanics of your instrument, is grounded in the real world. The mechanics of a piano or a bandoneon, or the biomechanics of moving your body around to pulses of sound in a milonga, are part of the structure of nature. And because they’re subject to the physical laws of nature, there are ways of studying them objectively. Can you guess where I’m heading with this? Don’t run away. I don’t like it either… but we’re going to have to take a moment to discuss… physics.

When we first began to look at tango technique in this chapter, we looked at static things like arm position and posture and center of balance—so all we needed was a little geometry. Now we’re beginning to look at motion, so we need to talk about three things: Gravity, potential energy, and acceleration. Let's get it over with:

We all know about gravity. If you go up to someplace high and step off, the force of gravity will pull you down, and maybe kill you. When you're up there, even if you don't fall, you have the potential to fall, so that means you have potential energy. And when you fall, you start to fall at a slow speed, and then begin to fall faster and faster. The speed that you fall increases, and that’s acceleration. There, that wasn’t so bad. Now let's use it to look at walking in tango.

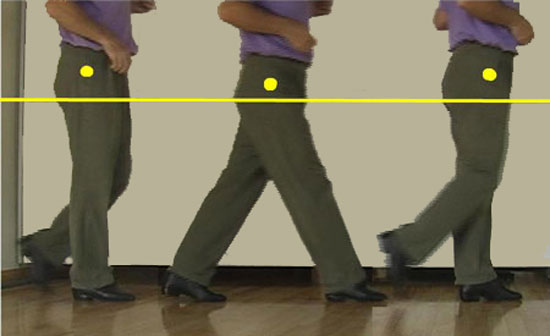

My body sinks goes lower when I step: The yellow point on my hip in the middle is slightly lower

than the first and last ones. When you walk tall on a straight leg, your body will always

sink down through the step, and rise up through the Zero Point as your heels pass.

I marked a spot on my hip with a horizontal line beneath it. It shows that, when I’m tall and balanced with my feet together at the Zero Point, my hip is a little higher. And when I have my legs stretched apart for the step, I’m a little lower. The reason is obvious—when your leg is vertical, you're taller, and the more your legs move apart away from vertical, the farther down you drop. But for this to happen predictably while walking, you must always support yourself on a straight leg. You need to begin on a straight leg the moment your foot strikes the floor, and you need to stay on it until all the weight leaves.

When I’m standing tall, with heels close, I have potential energy. Gravity wants to pull me down… but it doesn’t do it at a constant speed. As I tip forward and come down, the speed increases and I accelerate. So from the tall Zero Point, to the point where my foot strikes the floor, (the point of maximum leg separation), I accelerate down and forward. Then, as I move back up to my zero point, gravity slows me. My forward speed decreases until I stand tall at my Zero Point. Then the process begins again with the other leg: Lowest speed when I'm balanced up high with heels passing, high speed with my legs extended at my lowest point—which is just when my foot strikes the floor. Then the cycle repeats with the other leg. In short... I am a human roller coaster.

By continually clicking on the arrow on the right, you can see me ride over the top of a straight leg, and then accelerate back down into the next step:

then sinking and accelerating into the next step.

So we’ve returned to a common theme on these pages—the elements of tango as a natural phenomenon. The classic tango walk we’re describing is natural and efficient movement. Learn it, and you can dance with power night after night and conserve energy. Like a roller coaster., each step pulls you to its highest point, and then you coast down naturally the rest of the way. Walking naturally means returning to a high and balanced point with each step, falling downhill into the next, and then letting your momentum pull you back up.

This gives you three great advantages over normal walking. One is that you naturally slow and re-center yourself at the high point. This is the place where we usually pause or change directions in tango, so you slow and stabilize at the place where it's most needed. The second is that as you tip forward and accelerate using the weight of your upper body, the potential energy you gained standing up tall helps to carry your partner into her back step. She feels your lead as a small but clear surge forward from your chest, and then you both use that momentum to carry you back up to the top of the following step. And finally, the most important thing of all: We’ve seen that by walking this way, you naturally speed up as you “drop” into the step, and you naturally slow as you “climb” back up to your high point at Zero. This is a very, very beautiful thing—because it's a natural, efficient way to physically express the single most important part of tango.