Finding Zero

Timing and balance are at the core of almost every challenging physical activity. Hitting a tennis ball, or skiing quickly through a gate, are very different things, but timing and balance are fundamental to both. So let’s look at the specific kind of balance we need to dance tango. But first, I need to tell a sports story. (Sorry... but it does have to do with balance.)

For a while I fooled around with a sport called trials riding. It’s kind of like stunt riding on a bicycle, with lots of balancing and hopping around. The best riders can do amazing things—they ride right over the tops cars, and up walls, and over huge logs and boulders—but I just played around with it to improve my mountain bike handling. I’d go over to the park and practice getting up on the back wheel and hopping around, or jumping the bike off picnic tables. I finally gave it up after a separated shoulder, and two broken mountain bike frames. (They were expensive Litespeed titanium frames. The manufacturer replaced them—although when I read the fine print, I noticed that the warranty didn’t cover “stunt riding”. I think they got a little suspicious when I broke the second one.)

Trials riding legend Hans Rey in the desert, and riding his bike over a tank in Moscow.

One thing I learned at the park was how to stay balanced on the bike without moving. It comes in handy on rough trails. You can come to a stop, look around, hop to the side, or even turn around on your axis, and go back. And you can do it all “clean”—without unclipping from the pedals. It also comes in handy in track racing. Lately I’ve been going over to the velodromo in Parque Belgrano and riding the track a little. I’m out of shape and I’m no good, but I do have a good “track stand”. I can balance on the bike without moving, which is something that helps in the cat and mouse game of track sprinting.

When I was practicing, I’d find some grass, slow to a stop, and see how long I could stay clipped into the pedals without going over. At first, it wasn’t very long, but over time I got good. And as I stood there doing nothing, I thought about balance. (Sometimes standing still and not moving on a bike gets boring, so you have to think about something. I used to ride with a kid who practiced it so much that he got into the Guinness Book of World Records. Then he started doing shows at shopping center openings and things like that. He called it "The World's Most Boring Show." Of course, he could do other things. One time we were riding down a mountain and he yelled, "Bike limbo!", and started trying to crawl through the frame of his bicycle. We were going about 40 mph. He ended up joining a circus. True story.)

I found that some days I couldn't seem to stay balanced, and other days I could stay up forever. I thought that was very interesting. I’ve never seen a study about it, but it seems like balance comes and goes, just like strength and speed and quickness can vary from day to day. Anyway, here’s what I would do. I'd stare at a spot in the middle distance ahead, cock the wheel left, and then try to feel every tiny movement in my body. I'd become as still as possible, and imagine staying over a center point beneath me. I imagined it as a spot of light from a laser pointer, and I would try to keep it from moving. It took full body concentration. Sometimes I would even fall over if I moved my eyeballs. I'd look for the exact center of my balance, slow my breathing, relax, and try to remain completely still. The goal was to find and maintain the point of zero movement, zero effort, and zero imbalance. When everything came together, it even felt like time itself would go to zero—so I thought of it as finding the zero point. (Those of you who have read all these stories may remember when I climbed up on the Kilometer Zero monument in Congreso one night to practice. A few weeks ago, Alej and I met a couple from Canada at a milonga, and one of the first things they asked was, "Where the heck is that Zero monument? We walked all around Congreso looking for it.")

The thing I learned about balancing is this: At first, you can’t do it... and then later, you can—but only If you spend lots of time practicing! This is good news, because it means that no matter how bad your natural balance is, you can always get better with practice. And since being able to find and maintain your center is crucial in tango, working on balance is probably the single most important thing you can do to improve your dancing. So here we go. Let’s practice our zero point in tango:

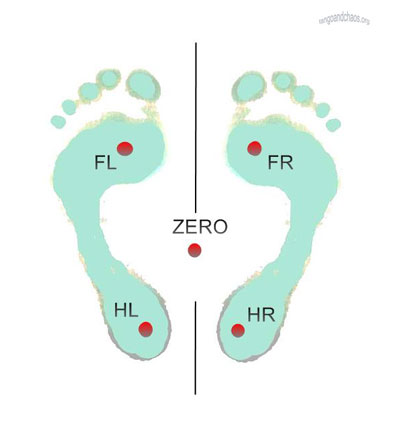

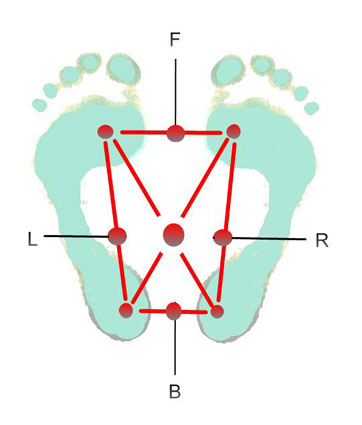

Five points of balance for practicing: Front Left, Front Right,

Heel Left, Heel Right, and Zero.

Find a good, centered, relaxed, "string" posture, and think about your Zero Point—the point of balance right in the center between the arches of your feet where it takes the least amount of effort to stand. Now let's name four other points: a left and right point to the front near the ball of each foot, and one on each heel (pictured above). Move your weight to one of them, and steady yourself over it. Front Right, Heel Left... it doesn't matter which one. Just pick one, and get used to how it feels to stay motionless, with your weight right over it. It won't be as easy as your Zero Point because it will take some muscle tension, but practice staying as still, relaxed and balanced as you can. Don't let your body bend at all. You should feel like a tall straight tree blown by the wind, tipping smoothly so that you lean slightly off center over the new position. Now, move to another point, and pause again. Stay at each position for about five seconds, until you feel very steady. Maybe the puppet master is moving the string attached to your head around, while your feet remain in place. Your weight shifts as you move around the pattern pictured below. Go in either direction, pausing until you are steady at each spot, and then return to Zero:

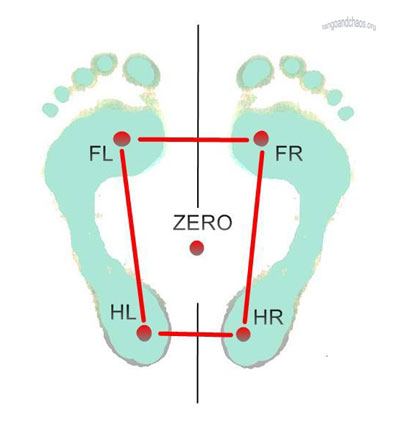

Follow the box pattern around, pausing at each point.

Now we'll add a couple of diagonal routes across the middle (below) so you can go from corner to corner. Move through the pattern randomly, swaying from spot to spot, pausing at each one. Go around and back, zigzag into the middle and back out. Be aware each time you cross your Zero Point:

Move randomly between five different points of balance.

Be aware of your zero point as you cross it.

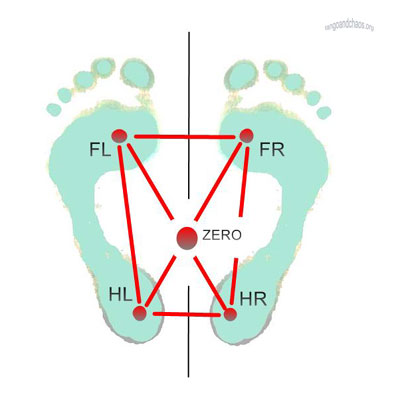

That's about it. We'll add four more points to the picture below, to the midpoints of each side, and mid-front and back. That makes nine different points to practice with. Move randomly between them, and become aware of them. Note how each brings tension to different bones and muscles. The side and midpoints are a bit easier, the corners are hardest, and Zero is easiest. Make sure to use good technique: Move smoothly, pause for a few seconds at each one until you are perfectly steady, and then move on. Don't lose your posture. Stay tall and relaxed, with your chest open and forward.

Nine points of balance. Become aware of them, and

practice until you feel steady and relaxed over each one.

You can do this drill any place and any time. If you do it regularly and concentrate on what your body is feeling, it will improve your balance, and you'll feel it on the dance floor. You'll begin to be aware of exactly where you and your partner's centers are as you dance. It may seem simple, but it has some very important and subtle applications for stepping—and stepping is the most difficult thing in tango. We'll talk about it later, but for now, get comfortable with this exercise. Try it in front of a mirror, and check yourself. You should look precise, smooth, and relaxed. Maybe a little silly, but maybe elegant too. Feel what your body is doing.

Sometimes, when you arrive over a point and steady yourself, play around a little. See if you can move your imaginary center-of-balance/laser-pointer in small circles around each spot, or write your name. You can even put on some tango music, and try to hit each point on a beat. You probably can't hit each consecutive beat, but try to arrive on one of them. Make tiny circles with your balance point you listen to the music. Get used to the feeling of matching what your body is doing to the melody. The upper body sways a little, and arrives over a spot on the beat. It pauses, stays very still, and then moves on. The time you spend on this will be more valuable than flying off to a workshop somewhere.